In terms of men and planes lost, the missions to Friedrichshafen (18 Mar 1944), Gotha (24 Feb 1944), and Berlin (29 Apr 1944) were the worst of the 285 missions the 392nd flew: 29 planes were destroyed, 135 airmen were killed, 127 were captured (with two dying while POWs), 26 were interned and 1 successfully evaded capture. The March 2011 News described Gotha; this issue focuses on Friedrichshafen. Berlin will be detailed in the next newsletter.

Much more information on these sorties is in the Missions and WWII Stories sections of www.b24.net; in the 392nd BG anthology, Twentieth Century Crusaders; and the book After the Liberators by William C. McGuire II.

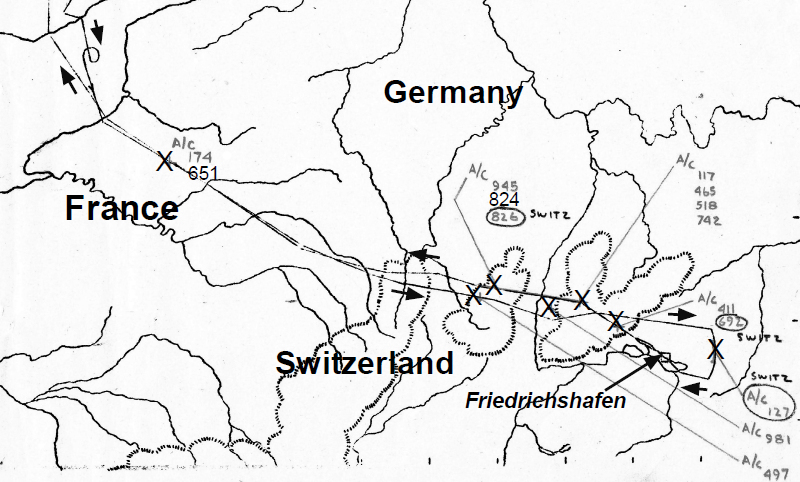

On 18 Mar 1944, 8AF dispatched 738 heavy bombers against eight airdromes and airplane component and assembly plants near Friedrichshafen and Munich, Germany. Per its Tactical Mission Report, “A common route over enemy territory to the general target areas was planned, with the three main forces separating to attack their respective targets and converging at the same points” for the return trip via the same route. “The route was essentially direct and was designed to facilitate fighter support, outflank the largest concentration of enemy fighters and avoid the strongest ground defenses.”

The 8th’s Narrative of Operations (8NoA) noted, “Penetration, target and withdrawal escort was provided by 598 P-47s, 113 P-38s and 219 P-51s. Included in this figure are 139 P-47s and 33 P-51s which flew second sorties.” Bombing was visual except on Friedrichshafen where an effective smoke screen and haze meant bombing had to be by Path Finder Force (PFF) radar.

“Enemy air opposition,” per 8NoA, “varied from weak to nil on most combat wings to very strong and determined on two wings. Encounters occurred principally in the target area and on the initial phase of withdrawal. Extremely aggressive and well-coordinated enemy aircraft attacks were met by the 14th Combat Wing.”

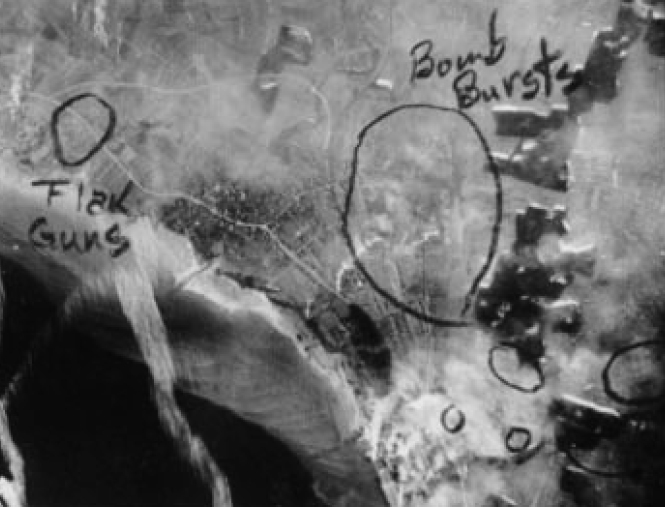

There was also “intense and accurate flak” at the target. After the planes landed, 8AF compiled reports from participating bomb groups. From the 738 planes, 8 crew members were killed, 35 were wounded and 438 were missing.

The B-24s (225 ships) made up the third force. Targets were the Dornier Werke assembly plant and the Maybach Motorenbau, Light Metal Casting Works at Friedrichshafen. Five P-47 and two P-38 Groups escorted the Libs.

Nine Liberator Groups bombed Friedrichshafen over a 20-minute period. Ground defenses were extremely effective, engaging every Group with accurate predictor controlled fire.

During the entire mission, only four to six enemy fighters were seen by the 2nd and 20th Combat Wings. The 14th CW was not so fortunate.

The target for the 392nd and 44th BGs was the Dornier plant at Manzell, two miles west of Friedrichshafen.

There, Do-217 flying boats and seaplanes were manufactured and assembled; in addition, the plant made components for bombers and perhaps for FW-190 fighters as well. The factory was also thought to provide components for the production of pilotless aircraft. It employed 4-5,000 people. Crews were warned that ninety flak guns were expected at Friedrichshafen.

The 44th was armed with 1,000-pound heavy explosive bombs while the 392nd carried 100-pound incendiaries. Of 54 a/c dispatched by 14CW, only 37 bombed the primary target. Results were good. The machine assembly shop, seaplane assembly shop and metal shaping shop of the Dornier plant were severely damaged. The engineering offices and electrolysis shop were also damaged and the seaplane basin was breached by a direct hit. Nine ships bombed targets of opportunity.

Per 2BD’s Tactical Mission Report, the 14th CW neared the target with the 44th BG leading the 392nd. The 44th was “well on their bombing run without encountering any AA fire when they were baulked by another formation turning across their line of approach and were, therefore, compelled to turn away to the right and circle round to make another run.

“The 392nd Group was flying some distance behind the 44th and came in to attack by themselves. They encountered very intense and accurate predictor control fire which quickly succeeded in knocking out engines in both the lead and deputy lead a/c, thus causing the whole formation to reduce speed considerably. This Group emerged from the target area in a bad condition with many of their a/c damaged, and when they were attacked by enemy fighters about twenty minutes later they were fairly easy prey.”

The 44th bombed soon after and also encountered very intense and accurate predictor control fire which seriously damaged many of their ships.

On this mission, 14th CW sent up just 24 percent of 2BD’s planes but suffered 78 percent of 2BD’s plane losses. On 20 Mar 1944, 2AD’s Commanding General and Division Staff met with the commanders of the 2nd, 14th, 96th, and 20th Combat Wings. One item discussed: “The fighters stated that the units were so separated it was impossible to cover it; that units were separated by 4000 feet in altitude; that while Group formations were fair, Groups were flying wide apart. Dense persistent contrails over Europe with some units not breaking into the clear until eight minutes before the target, forced Groups to altitudes other than briefed. Combat Wing assemblies have been weak regarding altitudes and separation between Groups. This affects fighter support as well as the maneuver at the objective.”

Resulting action required: “Groups within Combat Wings will fly as flat and as well-forward as possible. Combat Wings will maintain an interval of approximately three minutes. Leaders of Groups must make good designated Rally Points, otherwise there is no chance of catching up. Any changes in briefed route must be sent out on Channel B. (Aircraft standing-by on Channel C to relay changes in briefed route to fighters.) Combat Wings to reemphasize necessity for maintaining compact Combat Wing and Group formations. To be confirmed in 2BD Tactical Doctrine.”

Missing from the report was how to effect this policy in the face of heavy, accurate flak and massive, aggressive enemy fighter attacks.

The pre-brief for lead crews was held at 4:45am, for gunners at 5:30, and the general briefing for 28 crews at 6:00. The first plane took off at 9:55. The Group rendezvoused with the 44th BG as scheduled and took its place flying low and left.

579th CO Maj Myron Keilman was Command Pilot, flying with Capt Vernon Baumgart and crew (also 579th). He later wrote, “The bomb run was so designed that we would fly eastward past our Friedrichshafen target, then circle to the right toward the initial point (IP) of our bomb run on the east end of Lake Constance—about twenty miles from ‘bombs away.’ After bomb-release, we would make a right turn to assemble the group, then head out-bound for home.”

At 2:30pm, the 392nd uncovered for bombing and fell in trail of the 44th BG. “The bombardier was able to see the target area and landmarks and a visual run was made. [Then] all hell broke loose! Flak started bursting right in the formation. Not up ahead, above or below—they had us zeroed in. The concussions made our airplane buck as chunks of jagged steel clanged into it; and with that the other airplanes of the formation went sailing by. I was stunned at the havoc.

“Vern Baumgart, with his eyes on the flight instruments flying the bomb run, quickly recognized that we had lost power on #4 engine and promptly feathered it, along with applying full power to the remaining three. But the formation had overrun us and was scattered—the bomb run was in disarray. Lead bombardier [1/Lt Edward I. White] did his best to adjust for the sudden change in air speed and loss of programmed altitude, but it was too late. Needless to say, we didn’t get our bombs on the target.

“A north heading was taken out of the target for two or three minutes and it appeared that the rest of the Wing and whole Division had cut short of the rally point and headed home. The formation turned... Leaving the target area, our airplanes closed back in formation. Flying on three engines, we were about 10 mph slower. The groups ahead pulled away from us in a very short time.

“Earlier, because our 14th CW leader, the 44th BG, had been forced out of its lead position by another group cutting in at the IP, the 44th then had to do a 360-degree turn and come in for a second bombing run. This maneuver had created a long gap in the bomber stream, both ahead and behind us, thereby leaving us isolated and vulnerable. It invited the ensuing fighter attacks...

“There they were, a whole ‘gaggle’ of [enemy fighters] in close formation, paralleling our course about a half-mile to our right and climbing.”

Vern Baumgart remembered “those fighters coming on the right side. When they came in, they came in five abreast. I don’t remember ever seeing that before. They were literally wing tip to wing tip, five of them at a time straight on in. And every time they came in, somebody got hit.”

When Group Intelligence Officer Maj Percy B. Calley phoned the 2BD at 11:50pm with the 392nd’s Mission Narrative, he reported, “Flak at Friedrichshafen very intense and very accurate...chaff totally ineffective. Fighter cover was spotty and there was little fighter cover for a 30 minute period while group was under fierce attack. Enemy aircraft attacks came in waves with the planes attacking from head-on and above, going through our formation and then returning to attack from below and behind. About 50 Me-109s and FW-190s pressed the attacks energetically, but disappeared when P-38s came to our support, reappearing whenever the fighter protection was forced to go ahead of our bomber formation. Attacks began about 20 minutes after bombs away and continued for about a half hour—roughly from 2:50 until 3:30.”

Fourteen 392nd BG planes were lost with 70 men killed, 49 captured (with two dying while POWs), 26 interned in Switzerland, and one who successfully evaded. Claims against enemy fighters approved by 2BD were 23 destroyed, three probable, and two damaged.

Pilots 1/Lt Sidney Cohen (578th, in #42-109896, Gypsy Queen), 1/Lt Ward E. Mathias (576th, in #42-50670) and 1/Lt Charles L. Neff (576th, in #41-29433) aborted due to mechanical problems. All had flown far enough into enemy territory to get credit for the mission.

Two planes collided before reaching the target. 2/Lt John E. Feran’s plane (#41-28651, 576th) was seen falling back. Behind him, 2/Lt Gerald M. Dalton (#42-29174, Amblin’ Oakie, from the 577th) appeared to be caught in violent prop wash from Feran’s a/c. The planes collided, with Dalton’s cutting off the tail turret and tail assembly of Feran’s plane. The ships fell apart, collided again on the way down, blew up in sheets of flame and crashed.

Everyone in Feran’s plane was killed. Nine men in Dalton’s crew were killed, but waist gunner Sgt Charles F. Payne, who landed near Le Ployron, France, evaded with the help of the French underground.

He later wrote, “On the way to Friedrichshafen tail-end Charlie of our squadron peeled off and, since we were flying spare, we moved up into his position. Later he must have changed his mind, for he started back into France and he came back toward us and in about 15 minutes he was in formation on our left wing.

“I reported this move to the pilot, but he did not answer me. I could not figure out why neither he nor the co-pilot answered. The plane flew on our wing for a minute or so and then went under us.

“I began to get scared and called the pilot continually but still got no answer. The other plane started up as if to let us fly on his wing. Just before he hit us the bombardier called the pilot to pull up, and someone else called. The pilot still did not answer.

“The rudder of the other plane hit our right wing between the outboard engine and the wing tip, breaking the rudder and our wing. Our plane went up. I threw off my flak suit, grabbed my parachute, and reached for the waist window. The plane lurched and I was thrown against the side. The plane broke in two where I was standing, and I fell out at about 23,000 feet. I heard the other waist gunner scream. I felt for my parachute and found it was there.”

Payne also said that on its return from Friedrichshafen, his formation was above Le Ployron around 3:30 or 4:00pm. “By that time the Germans had lined up flak trucks on the road near the town. The formation seemed to turn right over this position. There were about 20 heavy guns.”

To avoid being hit by pieces from the two falling planes, 2/Lt Burrell M. Ellison (576th) made what he called a “screaming dive” in #42-7560, Blanid’s Baby/Little Joe, leveling off 2,000 feet below the formation. Unable to rejoin the formation because his #4 supercharger was out, he aborted. He was given credit for the sortie.

German fighter attacks began soon after bombing. Every gunner was literally fighting for survival so not much eyewitness information is available about the lost crews. The 577th Sqdn’s 1/Lt Lynn G. Peterson crew, aboard #42-7497, Old Daddy, was seen with one outboard motor on fire. It circled to the left, spun down and crashed. Three men were killed, seven were captured.

Ball turret gunner S/Sgt David R. Apgar later wrote his sister Emily from Stalag 3. He said, “...I am a prisoner of war in Germany. Our bomber got shot down, but I bailed out just in time before she blew up. I am wounded in the right arm, they got me on the second pass. But I’ll be all right in time, I am in a German hospital now and they treat us mighty fine. Don’t tell mom what happened if you can help it, just tell her I am fine.”

579th Sqdn 1/Lt William A. Kale and crew were on their first mission. After the #1 engine failed on the way to the target and the #2 engine had to be feathered a few minutes later, they diverted to Switzerland and were interned.

576th Sqdn pilot 1/Lt Donald K. Clover had lost one engine to flak but was staying in formation. After receiving several solid hits during the enemy fighters’ third pass, #42-52411 caught fire. When the bailout order was given, all eleven men left the plane. It exploded almost immediately after. Everyone made it down safely and became POWs. After the fighter attacks, the #3 engine on 41-28692 smoked, the right wing tank was leaking gasoline and the hydraulic system had failed. After taking violent action to avoid a collision, 576th pilot 1/Lt Walter T. Hebron Jr. could not regain the formation. He diverted to Switzerland, where the crew was interned, and was later awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for getting his badly damaged plane to a neutral country.

Flak and German fighters set 579th 2/Lt Dallas O. Books’ plane on fire and caused severe damage. The blast from an exploding oxygen tank pushed the only survivor out of the plane. #41-28742, Old Glory, exploded in the air soon after.

#42-7518, Hard to Get, was flown by 578th pilot 1/Lt Walter C. Raschke. It made a complete outside loop, went straight down and crashed. Eight men were killed outright. The other two were captured; S/Sgt Roy W. Davis succumbed to his injuries later that day in a German hospital.

578th pilot 1/Lt Bruce L. Sooy, aboard #42-99945, Pink Lady, was on the left wing of 1/Lt Rex L. Johnson, also 578th. He says Johnson, flying #42-52465, “either stalled or was hit with flak. His right wing went down then he nosed down sharply and passed under me like he was heading for Switzerland. That’s the last I saw of him.”

The crew did not make it to Switzerland. Only two men were able to bail out; the other eight men went down with the plane.

1/Lt William G. Sharpe, 579, and copilot 2/Lt Norbert A. Bandura were wounded in a fighter attack and were heard over the interphone discussing which one would (or could) fly the aircraft, #42-100117 (named Delayed Action or Sinister Minister or both). The plane crashed with seven men killed, including both pilots. Three men were captured.

By zigging and zagging, 578th pilot 1/Lt Clifford L. Peterson kept from getting hit on the first two enemy fighter attacks. On their third pass, though, #42-99981, B.T.O., was hit on the right side of the cockpit, blowing out the entire side. Peterson rang the bail-out bell. While he tried to control the ship, engineer T/Sgt Malcolm Hinshaw shot “pieces of fuselage as big as card tables” off a fighter. The enemy plane then skimmed over the top of the B-24 and collided with its two vertical stabilizers. The Lib went into a spinning, near-vertical power dive. Five men successfully bailed out from about 1,000 feet and were captured. Only Hinshaw escaped serious injury.

577th pilot 2/Lt Ellsworth F. Anderson and crew were attacked about 30 minutes after bombs away. During the melee, the plane’s flight controls were knocked out. Seven men were killed and three became POWs when #42-109824, The Arsenal, went down.

#42-109826, Late Date II, was flown by 577th pilot 1/Lt George T. Haffermehl. It was badly damaged by fighters— bullets shot up the #1 engine, the oxygen system, and hydraulics. After ringing the bail-out bell, he and four men abandoned ship. One was killed when his chute failed to open; the others became POWs. Copilot 2/Lt Donald H. MacMullen got the plane to Diessenhofen, Switzerland, where he and the four remaining crewmen were interned.

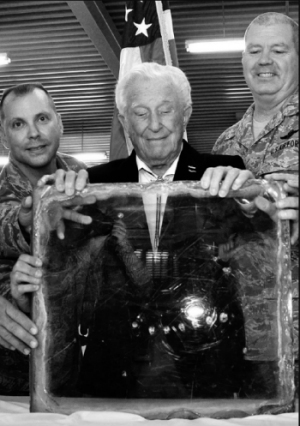

Bruce L. Sooy, now 97, says the Friedrichshafen mission “is on his mind like it happened yesterday.” When the lead planes each lost an engine, his speed went from 192 mph to 130 mph. “Aircraft were scattering like quail, some going down. Flak was so heavy and accurate it looked like a heavy rain cloud. Then, the FW-190s hit us. They came across in elements of five. We took heavy hits on the first pass losing #2, 3 and 4 engines and my right rudder. If the fighter pilot had fired a fraction of a second sooner everything would have come through the cockpit and I wouldn’t be here. We were lucky. Everyone got out safely, all the chutes worked.”

[Photo on the left] On 8 Apr 2014, members of the 70th and 79th Air Refueling Sqdns at Travis AFB in California presented a piece of his windshield to 578th pilot Bruce Sooy. Bullet marks from 18 Mar 1944 are still visible. The Travis AFB Heritage Center arranged for an airman at Ramstein Air Base in Germany to pick it up from Karl H. Matt, who grew up near Sooy’s crash site. After seeing the windshield in a friend’s barn, Karl convinced him “that it would be better to have the windscreen on display in a museum than to be hidden in a barn.” It was flown to California by a crew from Travis, where it will soon be on display at the Heritage Center. Photo by SSgt Cindy G. Alejandrez, 349th Public Affairs

An article in the 19 Mar 1944 issue of Stars & Stripes described the mission. “Friedrichshafen, just across Lake Constance from Switzerland, was hit by United States heavies.... It has aircraft industries and a big radio location plant. Liberator crewmen upon their return told of encountering much savage opposition.”

2/Lt James E. Muldoon, 578th, recounted that “his formation of 12 bombers was attacked head-on by about 75 enemy fighters. His own escort had pulled ahead when the Liberator formation slowed down to protect two crippled planes.

“This was the chance the enemy was waiting for. They hit us in a solid mass. A 20-millimeter shell came through the co-pilot’s window and set off the abandon ship bell. Smoke and flames filled the nose of the ship. I saw several Liberators go down.”

Hearing the alarm, two of his men parachuted out of #42-100100, Double Trouble, and became POWs. Muldoon successfully nursed the plane back to Wendling. Waist gunner S/Sgt Stephen A. Bednarcik was later credited with destroying two Me-109s.

Other crews who limped back to Wendling also described fierce gun battles.

What 577th pilot 1/Lt Dexter E. Tiefenthal and crew endured was later described in a 392nd BG press release: “Pierced in 2,500 (correct) places by bullets, shells and flak, carrying five wounded gunners and credited with destruction of four fighters and a probable, the Liberator [#42-99989] Son of Satan limped back from Germany recently, its destination the scrap heap. The story of the bomber’s battle with enemy fighters is an epic of heroism and achievement in one of the fiercest air battles in this Liberator Group’s annals.

With 25 shell-holes more than a foot and a half in diameter, the Son of Satan was so badly damaged it will never fly again. Dismantled, the parts of the Liberator that can be used will be salvaged. The rest will be junked.

Forty Me-109s and FW-190s attacked the Liberator formation as it made its way back from bombing targets in southwestern Germany. Sweeping in with a mass attack on the aircraft, they killed one waist gunner on Son of Satan almost immediately, fatally wounding another. For a moment the waist positions were defenseless. As the enemy closed in for another attack, the ball gunner, unable to stay in his belly turret due to an oxygen leak, took over in the waist, manning first one gun and then the other, moving from side to side as the fighters pressed in. The pilot was taking violent evasive action. “I saw Libs maneuvering in a fashion I never expected,” the copilot said. “One seemed to be doing an inside loop while another stood almost upright on its tail.”

In the top turret, the radio operator was hit. He had just climbed into the turret ordinarily occupied by the engineer as the latter checked the transfer of fuel from reserve tanks. Wiping the blood from his eyes with one hand, the radio operator fired the guns with the other. For 15 minutes, he remained in the turret warding off the attacks of the fighters. Later when the danger had passed, he acted as a communications link between the flight deck and other sections of the bomber, replacing the shot-out interphone. Meanwhile, he refused to leave the turret.

In the waist, the ball gunner was hit several times in the legs and back in the enemy’s second assault. Unable to stand, he continued to fire from his knees.

The tail gunner was flying in that position for the first time. Too big to wear a flak suit, he had thrown the back of the suit over his shoulders. In the first attack, an Me-109 cut it right off his back. The flak suit was ripped to ribbons, but the gunner was unhurt. “I spotted a fighter cutting across in front of me just about that time,” the tail gunner said, “and I let him have it. He blew up. Then they gathered for another attack, this time coming in from the tail of the formation,” he continued. “I thought there were about 40 of them all headed for the Son of Satan. I fired at one only, and saw him explode.”

Close on the destruction of the second fighter, a second 20-millimeter shell burst inside the tail turret, knocking the sergeant out of position. Bruised and dazed, he began to climb back to his turret when another 20-millimeter tore through, tearing metal, splintering glass and ricocheting past his head. Slightly stunned, he looked across the 10 feet of space between him and the waist gun positions. He found the ball gunner on his knees, trying to raise himself to the guns, the two waist gunners at his feet. Stumbling past the waist gunners, the Sergeant gently lifted the ball gunner away from the guns and forced him to lie down. Picking up extra flak suits, he placed them over the two men still alive. At that point, two fighters made another pass at the left waist gun position. The tail gunner manned this gun, opening fire at 800 yards. One fighter burst into flames, going down in a spin; the other had enough and peeled off without pushing his attack. The wounded men demanded attention. Bandaging their wounds, the tail gunner reassured them, making them as comfortable as possible.

Up in the nose of the bomber, the fight had been equally fierce. Two head-on attacks had given the nose gunner all he could handle. Both guns were hot from almost continuous fire as he forced the enemy to keep a safe distance. Two more aggressive fighters had come in closer than was safe, however. Seared by the 50-caliber bullets from the nose turret, they had exploded, breaking into pieces as they hurtled down out of control. [Nose gunner S/Sgt James J. Osterheldt was later credited with destroying 2 FW-190s and probably destroying another.]

The enemy left. The pilot and copilot, trimming the damaged bomber as best they could, checked on the injuries to the aircraft. Son of Satan’s tail and fuselage had more holes than solid surface, the engineer reported. By masterful work at the controls, the pilots kept the bomber in formation until they crossed the coast of England. Heading for the nearest base [Gravesend, Kent], the pilot found the landing gear would not go down. He instructed the engineer to let the gear down with the emergency hand crank. By this means, the right wheel was let down, but the engineer found the cable for the left wheel had been shot away.

Ordering the nose wheel kicked down, the pilot decided to land on the nose and right wheels, hoping to keep the left wing off the ground until speed was lost. Setting the bomber down gently, the pilot guided the aircraft to the far end of the runway, before the left wing began to lower. As the wing tip touched earth, ground crews watched breathlessly, breaking the tension when the big Liberator came to a stop, slewing around in the opposite direction.”

577th pilot 1/Lt George M. Brauer was flying #42-73505, Fairy Belle. In his diary, engineer T/Sgt Emilian W. Larue wrote of seeing “about 75 Me-109s coming in for attack. I knew then I had flown my last mission. Strangely I was not afraid of death, the ship is quiet and the ack-ack sounds like hell in my turret.”

Larue continued, “Lt. [Lynn G.] Peterson flying our left wing is hit bad. His #1 engine on fire. At this point Lt. Peterson tried to gain protection from us by flying close to us so we could give him coverage with our guns.” But, “We could hardly handle ourselves. He saw he was going to set us afire if he blew up. So he rocked his wings showing he was dropping out. Eight chutes going out. The ship went into a sharp dive, three Me-109s jumped him and finish[ed] him off. Our guns were going to beat hell.

“We knew it was our last. Jerries concentrated attack on our ship. Tail gunner shot one down, waist gunner got another. I look in my ammunition cans and started to sweat, my ammunition about gone. My ear cut bad and blood keeps getting in my eyes and on my goggles. I missed a fighter coming in at six o-clock, my tail gunner nailed him. We were under attack for an hour.

“Over France, our P-38s, P-47s and P-51s came in and gave these damn jerries hell. They shot down nine I could see. I got out of my turret and checked my ship. Crew ok. A 20mm hole in left [side], a few bullet holes and flak holes, oil leaks and shot up rudder. We got past Paris and ackack gave us hell again. Finally hit Channel. We finally hit home.”

Tail gunner S/Sgt Wilbur W. Rachell later received credit for destroying two Me-109s.

579th Sqdn bombardier 2/Lt Robert C. Lory was in the nose turret of #42-109814, Jive Bomber, flown by 2/Lt Joseph F. Darnell Jr. He “saw FW-190s; they looked like a P-47. They attacked us from 12 o’clock high, and moved through us, five abreast tracking the group.

“They began sharpshooting us down. Fortunate for me, on that first pass I was able to fire at one of the planes. Anyway, after that first pass, my turret stopped. The guns, instead of moving, were now parallel to the wings of the aircraft and I couldn’t get it to move, so I just sat there and was a spectator. I saw them line up again and make another pass through our group. They knocked down more airplanes.

“By that time I looked around and said, ‘Oh my God, we’re losing everybody. We’re going to get shot down.’ Then they lined up for a third pass, and about that time we were hollering, ‘Mayday! Mayday! Where are our fighters?’ And all of a sudden, out of nowhere, come these P-38s. Boy, were we glad to see them. They tangled with the German fighters and broke it up.

“In the meantime we got out of there. As we went out there were eight of us leaving the combat area. Somewhere along the line one of the eight disappeared. When we got to England and crossed the coast, there was a landing strip there. That other plane that was left with us, crash landed down there. So there were only six that got back to the base. When we got back everyone was saying, ‘Where’s the rest of them?’ We kept pointing back East, they’re back there somewhere.”

576th plane #42-100371, Doodle Bug, had been cripped by flak even before the first fighter attack. Despite having at least one engine out, pilot 2/Lt William E. Meighen got the plane back to England, landing at an RAF fighter base at Biggin Hill, Kent.

No accounts are known of what 1/Lt George Spartage and crew, 579th, endured. However, #42-99990, Short Snorter, was so badly damaged that it didn’t fly again until early May. Ball turret gunner S/Sgt John W. Ridgeway Jr. was credited with destroying two Me-109s.

2/Lt Hubert F. Morefield and crew (578th) were flying at the rear of the formation in #42-50604. When three FW-190s attacked simultaneously, tail gunner S/Sgt John H. Blekkenk drove two away and destroyed a third.

Waist gunner Sgt Herman A. Breithaupt later summed up the mission: “We really got the shit shot out of us today. About fifty fighters jumped us after we left the target. We were hit several times but none very serious except the one that started the fire in the tail end of the plane [causing first and second degree burns on Blekkenk’s face and neck]. I got the fire out and we came on home.”

Deputy Lead Capt Wyeth C. Everhart and crew, 579th, were aboard #42-52605. In his Lead Navigator’s Narrative, 2/Lt Harold C. Kornman wrote, “On approaching the target area we swung wide on the right turn into the target and at 2:15pm we started throwing chaff to disguise the turn. We stayed outside of the briefed circle into the I.P. and made a visual run on the target... Flak over the target was very heavy and very accurate. The lead ship was hit near the target and the air speed dropped to 135 and 140 mph.

Bombs were dropped at 2:38pm at 19,000 feet and at 2:40 our #3 engine was feathered. We made a right turn at the target... and then headed [to base]. At 2:57 we encountered 30 enemy fighters which stayed with us until 3:27. At 3:15 the lead ship dropped back and we (the deputy lead) took the lead.” They landed at 6:10pm.

Flying on three engines, the last plane to get back to Station 118 that day was #42-7510, El Lobo, with Command Pilot Maj Keilman and pilot 1/Lt Baumgart. The Lib had been hit in the left wing and lost a lot of fuel. Keilman and the engineer debated whether there was enough gas left to get them back to England or if they would have to divert to Switzerland. Finally, Keilman decided “that we could reach the White Cliffs of Dover, then we would worry about a place to land—or bail out.”

Keilman said, “Nine hours after take off, our safe landing was an event that was as welcome as any in my life.” It was especially momentous for the Baumgart crew, as Friedrichshafen was the 25th and final mission of their combat tour.

577th Sqdn armorer S.J. “Sandy” Elden, who had loaded bombs on the planes that morning, said, “Our saddest day was undoubtedly the Friedrichshafen raid. Very few aircraft returned and total disbelief permeated the entire base. There was a profound silence throughout all quarters.”

578th Sqdn Intelligence Officer Capt Holmes Alexander echoed those comments. March 19, 1944, he wrote, was a “bright Sunday” but there was “an air of hushed and sober depression everywhere.”

A two-day stand down for the Group was ordered. On 21 March, just thirteen crews flew a No Ball mission to Watten, France. That same day, nineteen replacement crews were ordered to the 392nd.

Sandy continued, “As a result of this tragedy, the workload of almost all the ground support sections reduced dramatically. We had virtually no aircraft to service and several weeks passed before we were back to full strength. Replacement aircraft were no longer camouflaged. All our new B-24s were bare metal, a bright silver color.”

Even before the war ended, US Army Graves Registration units moved throughout Europe to find the burial places of American military personnel, establish their identities, and ultimately bury them per their next of kin’s wishes.

By late 1951, the Army was able to identify all but eight of the 392nd BG’s casualties from the Friedrichshafen mission. By process of elimination, they knew who the men most likely were but could not identify them individually.

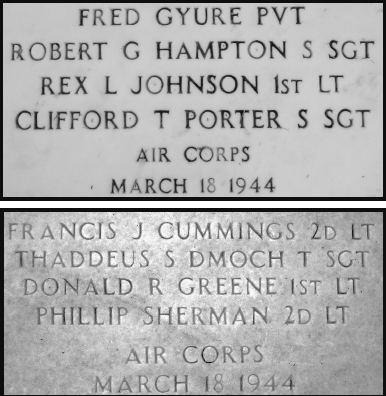

They were thus buried in group graves at Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri. In one grave were the remains of Feran crew navigator 2/Lt Francis J. Cummings, radio operator T/Sgt Thaddeus S. Dmoch, bombardier 2/Lt Donald R. Greene and Dalton crew navigator 2/Lt Phillip Sherman.

In three graves, but sharing a single headstone, were pilot 1/Lt Rex L. Johnson, Raschke crew tail gunner Pvt Fred Gyure, and Books crew gunners Sgt Robert G. Hampton and S/Sgt Clifford T. Porter.

Many years later, Command Pilot Myron Keilman said, “The consoling after-thoughts of the 392nd’s most disastrous mission are that several 2AD B-24 bombardment groups made devastating hits on the primary objective, and Friedrichshafen was never re-scheduled as a target” for the 392nd.